Difference between revisions of "Text Directionality Workgroup"

(→Text transformation) |

(→Text transformation) |

||

| Line 280: | Line 280: | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

| − | <ab style="transform:rotate(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab> | + | <ab style="transform:rotate(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab> |

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

[[Category:Council]] | [[Category:Council]] | ||

Revision as of 18:48, 1 November 2013

Contents

Text Directionality Workgroup

This page will summarize the evolving work of the Text Directionality Workgroup, tasked by the TEI Council with developing a new section for the Guidelines on recommendations for encoding a variety of textual features related to text directionality and orientation. The related SourceForge ticket is https://sourceforge.net/p/tei/feature-requests/342/.

MDH made a presentation to the TEI Council on this topic during the April 2013 Council meeting in Providence.

Workgroup Members

- Martin Holmes (TEI Council)

- Deborah W. Anderson (Unicode Consortium)

- Robert Whalen (Northern Michigan University)

- Marcus Bingenheimer (Temple University)

- Stella Dee (King's College, London)

Order of Tasks

- Enumerate textual features to be covered

- Collate existing standards and recommendations and relate them to features

- Identify any gaps which might require new TEI elements or attributes

- Outline the new section

- Write the first draft for consideration by Council

- Identify other places in the Guidelines where information or links need to be included

Mailing List

The group has a mailing list provided through Brown University at http://listserv.brown.edu/archives/cgi-bin/wa?A0=TEI-DIR-WG.

Notes from discussions

- We agree (so far) that we would like to distinguish between two distinct types of phenomena: "true" text directionality (such as that found in language such as Japanese written vertically ttb with lines sequence rtl -- and "transformational" features, in which text written in any direction is rotated or written along a path. Our proposal will have to cover both of these phenomena, and provide for cases in which they interact, but they will probably be handled by different mechanisms.

- We agree that the ITS specification is rather a red herring. Its primary concern is translation rather than text representation, and its provisions for directionality are sparse.

- We agree that the CSS Writing Modes draft provides the best descriptive introduction to directional phenomena. The general consensus is that we should base our analysis of the phenomena on CSS Writing Modes, and probably base our recommendation on its properties and values, expressed using the TEI @style attribute.

- We agree that the CSS Transforms draft provides the best approach to describing 2D and 3D rotation, skewing, and similar transformational features, and we will provide some simple examples showing how to use these features, and how they might interact with true directionality features.

If we do base our recommendation on the properties and values specified in CSS Writing Modes, then we have three possible approaches in our recommendation with regard to text directionality:

- We could recommend the creation of multiple new attributes, one for each property in CSS Writing Modes. This would enable us to add more attributes if there are features we want to describe that are not actually handled by CSS Writing Modes.

- We could recommend the creation of a single attribute, e.g. @cssWritingMode, whose value could be any valid combination of the CSS Writing Modes properties and values (in other words, its content would be a CSS ruleset constrained only to the properties relevant to writing modes).

- We could recommend that people use the existing global @style attribute, which is already available for CSS code (although it is not tied to CSS). This would enable users to combine CSS Writing Mode features with other CSS code which applies to the same element.

No. 1 seems too complicated; we'd end up with lots of new attributes, whose values would inevitably need to be combined anyway during any rendering process.

No. 2 is attractive in the sense that it keeps text directionality features separate from other CSS-specified features, and would allow the user to combine writing mode information with a use of @style which didn't happen to use CSS.

No. 3 seems the most attractive in that it's very simple, and involves no change to the existing TEI infrastructure at all; we just need to explain and illustrate how to use the properties, and point users at the W3C specification. MB points out that we are thereby assuming that @style is using CSS3 (since Writing Modes is not available in early versions of CSS); it would therefore be helpful if the styleDefDecl element were able to specify not only @scheme="css" but also the version (perhaps @schemeVersion="3") for clarity's sake. However, it appears that since CSS is now modular, it may not be possible to specify a global CSS level and stick to it, since a module defined in level 3 may be used alongside one which is only available in level 4.

Examples, constructed and from primary sources

This section collects together some examples which our discussion can reference. We aim to collect useful examples of some straightforward cases, but also of some edge cases which our proposal must be able to handle. Some of these may be used as examples in a final draft of the new section of the Guidelines. These are listed in no particular order.

Text directionality

- Wikipedia has some good examples of Boustrophedon (alternate lines running in different directions, with glyphs also flipped horizontally for rtl lines).

- Ancient Berber is an example of a script written bottom-to-top, with lines right-to-left.

- This Berber inscription also incorporates rotation, so we could demonstrate the combination.

- Rongo Rongo (Easter Island, reverse boustrophedon)

Rotation

- Rotation along X axis:

"tei-c.org" 180 deg: "ʇǝı-ɔ˙oɹƃ"

"tei-c.org" 180 deg: "ʇǝı-ɔ˙oɹƃ" - Rotation along Y axis:

- Rotation along Z axis:

- Easter Wings is a good real-world example of rotation along the z axis.

- Arabic text written along a circular path (a roundel).

- The Phaistos Disc (spiral writing)

- Ogham (clockwise from bottom left)

Useful documents

- UTR 50, Unicode Properties for Horizontal and Vertical Text Layout

- Forum for UTR 50

- UAX 9, Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm

- Proposed update to UAX 9 for Unicode 6.3

- Unicode BIDI forum

- UTR 20, Unicode in XML

- What you need to know about the bidi algorithm and inline markup (W3C)

- Unicode controls vs markup for bidi support (W3C)

- CSS Writing Modes

- CSS vs Markup in XHTML

Other notes

Deborah points to four new bidi isolate characters to be added to Unicode (probably 6.3), and quotes this description:

HTML/CSS recently introduced “bidirectional isolates” to improve handling of bidirectional text in HTML. However, this new technology does not provide a means to solve the bidi issues in non‐HTML documents or when copying and pasting HTML into plain text. This proposal requests four format characters that can be used to support formatting of bidirectional text in non‐HTML documents and plain text, in a way which can be interoperable with the mechanisms used by HTML/CSS for markup.

This is in addition to the five bidi codepoints (LRE, RLE, LRO, RLO, and PDF). They are described in proposed update to UAXZ #9.

Preliminary drafts of Guidelines sections

Early drafts will be presented here for discussion and editing.

vi.3: Text directionality

Introduction

Scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the direction in which these glyphs are to be read. The majority of modern languages are written from left to right within the line, and have their lines stacked from top to bottom vertically (English, Russian, Greek), but there are several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew), while also stacking lines top-to-bottom. Some east Asian languages such as Japanese and Chinese can be written with the same directionality as English, but are often also written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left. There are a few cases of bottom-to-top writing, such as Ancient Berber, and some Ogham inscriptions; there are even instances of writing which changes direction on alternate lines (boustrophedon, discussed in detail below).

When a language or script can be arranged in two or more different directions, there are often other consequences arising out of the choice; for example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used, whereas in vertical writing an alternative glyph, U+FE11, may be used to ensure that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. In addition, scripts which normally have a single directionality (such as English) may be written in a different direction in the context of another language (English words inserted into vertical Chinese text, for example), or in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, in which column or row labels may be written vertically to make the most effective use of available space.

The directionality features of scripts, and the consequences arising out of them, are generally referred to as "writing modes". For many documents encoded in TEI, there may be no need to encode any information relating to writing mode, because it will be obvious. Modern printed texts in most European languages, for instance, may be expected to use left-to-right/top-to-bottom directionality; Arabic or Hebrew texts are expected to run right-to-left/top-to-bottom. Directionality can be reliably deduced from the language and script settings, and these are probably already encoded using the @xml:lang attribute in TEI documents. Even in the case of many "mixed mode" documents (documents in which languages or scripts with different writing modes are mixed together), it may not be necessary to be explicit about directionality. Consider the case of an English text containing a few Arabic words--what is termed a "bidirectional" text:

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

Since Arabic is never written from left to right, we can assume that the Arabic glyphs are to be read in that direction, even if they are in the context of a left-to-right English sentence. In fact, most codepoints in the Unicode standard have a specific directionality setting which helps any rendering engine to determine how they should be ordered. The Latin glyph "a" has a bidirectionality setting of strong left-to-right; the Hebrew א (alef) is strongly right-to-left. Other glyphs have weak or neutral settings because of the contexts in which they may appear. The Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/) provides a complex series of rules enabling user agents to render mixed-mode texts with predictable and reliable results, based on the bidirectionality class values of their glyphs.

In many mixed-mode texts, though, the Bidi Algorithm may not give the desired results. To deal with this, Unicode provides a set of "directional formatting characters" (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/#Directional_Formatting_Codes), which are additional codepoints whose only function is to signal to a user-agent that a specific directionality setting should be turned on or off. These can be inserted into a text to influence the outcome of the bidirectional algorithm. However, in the case of documents encoded in XML, the W3C explicitly advises that markup rather than directional formatting characters should be used ("In (X)HTML and XML do not use the paired Unicode bidi formatting code characters where equivalent markup is available," http://www.w3.org/International/questions/qa-bidi-controls). We concur with this recommendation, and the remainder of this section and the next provide a set of encoding strategies for handling text directionality without the use of directional formatting characters. The approach we recommend is based on two external specifications, in line with our normal practice of incorporating existing standards where they are available and appropriate. Those specifications are the CSS Writing Modes module (http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css-writing-modes/) and the CSS Transforms module (http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-transforms/). Since (at the time of writing) neither of these modules has yet reached the stage of a Recommendation, the advice offered below should be regarded as provisional, and you should check your usage of the properties concerned against the current version of each specification where possible.

The following sections will present a few simple examples of phenomena relating to text directionality and transformation, along with some suggested encoding strategies based on the following CSS properties:

direction: ltr | rtl

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

text-orientation: mixed | upright | sideways-right | sideways-left | sideways | use-glyph-orientation*

unicode-bidi: normal | embed | isolate | bidi-override | isolate-override | plaintext

- The value "use-glyph-orientation" may be dropped from the CSS Writing Modes specification.

In the following examples, CSS rules are encoded in the global TEI @style attribute, which applies them directly to the element on which they are specified (and in most cases, its descendants). It is also appropriate, and will often be more efficient, to express the rules in TEI <rendition> elements in the <teiHeader> and point to them using @rendition attributes.

Horizontal directionality

Returning to our previous simple example

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

we could use the direction property to make directionality explicit:

direction: ltr | rtl

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">The Arabic term </seg> <seg xml:lang="ar" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">قلم رصاص</seg> <seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">means "pencil".</seg>

</syntaxhighlight>

The use of the direction property is straightforward, but the unicode-bidi property requires some explanation. These three segments are all inline; they form part of a single sentence, although they happen to be encoded on separate lines in this example. The default value for unicode-bidi is "normal", and the CSS Writing Modes specification stipulates that the direction property "has no effect on bidi reordering when specified on inline elements whose unicode-bidi property’s value is normal, because the element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm." In other words, if we want to make it clear that the direction property is effective here, we must include a value for unicode-bidi which will make it so.

However, as mentioned above, all of the directional encoding in this example is superfluous; ambiguity does not arise in this particular case. Moreover, "ltr" is the default value for the direction property, so we do not need to specify it. However, consider the following example, in which Hebrew and English text are mixed. (This example is presented in the form of graphics, because we cannot rely on user agents that may be rendering or displaying these Guidelines to provide a consistent output.)

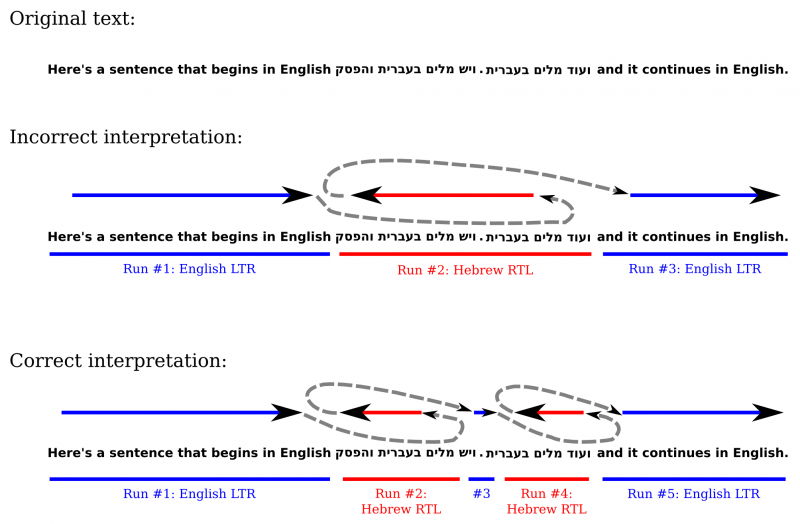

Here, an English period appears in between two runs of Hebrew text. Should that period be interpreted as part of a single run of right-to-left text, or should it be deemed to terminate the first run and precede the second? In the Unicode Bidi Algorithm, punctuation is not strongly directional; it inherits directionality from the surrounding characters. If, therefore, we interpret the example as a sequence of three runs (English, Hebrew, English), we arrive at an incorrect interpretation. This is what the Unicode Bidi Algorithm would generate if not provided with any additional clues. The correct rendering requires that we delimit the two Hebrew runs separately, like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

Here's a sentence that begins in English <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">ויש מלים בעברית והפסק</seg>. <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">ועוד מלים בעברית</seg> and it continues in English.

</syntaxhighlight>

Here the English is unmarked for directionality, but the period is clearly not included in either of the RTL runs, so the ambiguity inherent in the plain text is avoided.

[Would it be helpful to have another example presenting ambiguity arising out of the use of a g element at the end of a text run?]

Vertical writing modes

So far, we have looked only at left-to-right and right-to-left text running horizontally, using the direction: ltr|rtl property. However, there are many scripts and languages which are written vertically (mostly top-to-bottom, but with a few unusal examples running bottom-to-top, as we shall see below). Handling vertical directionality requires the use of another CSS property, the writing mode:

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

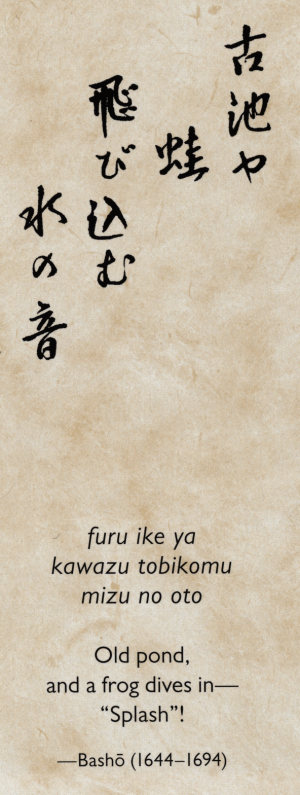

The values for this property include two components: "horizontal" or "vertical" specifies the inline writing direction, while the second component specifies the direction in which lines in a block, and blocks in a sequence may be arranged: from top to bottom (as in most European languages, in which lines and paragraphs are arranged from top to bottom on a page), from right to left (as in the case of some East Asian languages such as Japanese, which we will see below), or left-to-right (e.g. Mongolian). This example shows a Japanese haiku poem transcribed first in Japanese, then in Romaji (Japanese in Latin script), and finally in an English translation.

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl" xml:id="furu-ike-ya_jp" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_romaji #furu-ike-ya_en"> 古池や<lb/> 蛙<lb/> 飛び込む<lb/> 水の音 </ab>

<lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb" xml:id="furu-ike-ya_romaji" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_en"> <l>furu ike ya</l> <l>kawazu tobikomu</l> <l>mizu no oto</l> </lg>

<lg xml:lang="en" xml:id="furu-ike-ya_en" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_romaji"> <l>Old pond,</l> <l>and a frog dives in—</l> <l>"Splash"!</l> </lg>

<bibl>—Bashō (1644–1694)</bibl>

</syntaxhighlight>

Note: for the sake of simplicity, the indenting of lines in the vertical Japanese has been ignored in this encoding, since this section focuses on language and writing mode issues. The Japanese transcription has writing-mode: vertical-rl, which is required because Japanese may be written either in this mode or horizontally. The transcription in Romaji has @xml:lang="ja-Latn" (Japanese written in Latin script) and has a horizontal writing mode; this may seem superfluous, but vertically-written romaji is not unknown.

Vertical text with embedded horizontal text

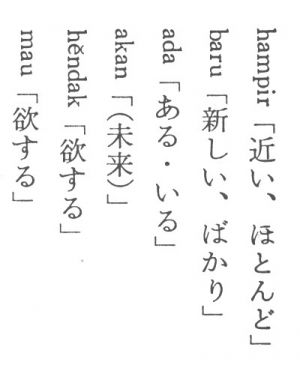

When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters the two orientations; punctuation for instance needs to be positioned differently in vertical versus horizontal text). However, it is very common for languages written vertically to have embedded runs of text from languages normally written horizontally. This raises the issue of the orientation of the glyphs from the horizontal language. Are they written upright, as they would normally appear in horizontal text runs, or are they rotated? Consider this fragment from a Japanese article about the Indonesian language, which takes the form of a glossary list:

This might be transcribed as follows:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja"

style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: mixed"> <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item>

<label xml:lang="id">baru</label> <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item>

</list> </syntaxhighlight>

The rule text-orientation: mixed gives the expected orientation: "In vertical writing modes, characters from horizontal-only scripts are set sideways, i.e. 90° clockwise from their standard orientation in horizontal text. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation" (CSS Writing Modes). In actual fact, the default value for text-orientation is "mixed", so this rule is not strictly required, but if the Indonesian glyphs had been set vertically, like this:

then the encoding would have to be explicit, and we could capture the orientation with text-orientation: upright.

Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts

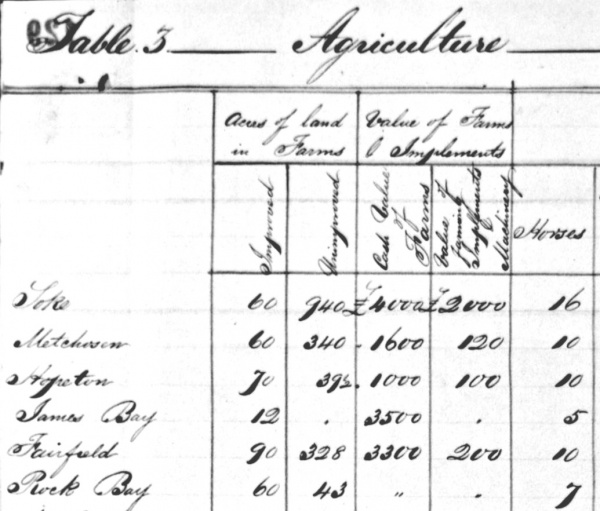

It is not uncommn to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where it is not embedded in a vertical text run. This example is a fragment from a table of information about agricultural development on Vancouver Island, written in 1855:

Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page. This is not a "native orientation" for English; readers would not find it easy to read this text, and might be inclined to rotate the page in order to read it in a more natural way. To describe this sort of phenomenon, we can use the text-orientation property again:

text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation

For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode one of the four cells containing vertical text like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> Cash Value<lb/> of<lb/> Farms </cell> </syntaxhighlight>

The writing-mode captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its line/block flow is from left to right (so "of" is to the right of "Cash value"), while the text-orientation value encodes the orientation (rotated 90° counter-clockwise). We might also add text-align: center to the style, to express the fact that the text is centrally-aligned; alignment properties are mapped relative to the line flow, so the word "of" is visibly centred relative to the physical top and bottom of the box, which are the left and right from the point of view of the line flow.

Bottom-to-top writing

There are a very small number of scripts which appear to be written bottom-to-top; perhaps the most well-known is Ogham, an alphabet used mainly to write Archaic Irish. The CSS Writing Modes specification does not explicitly provide for the distinction between top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top in vertically-written scripts; it is argued that all instances of bottom-to-top scripts are actually left-to-right horizontal scripts, oriented vertically because of the constraints of the medium on which they are inscribed (as in the case of Ogham inscriptions on tombstones). In other words, the case of scripts like this is analogous to the vertical English text-runs in the table cells in the example above, and can be handled in exactly the same manner (writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left).

Summary

In this section, we have presented one approach to encoding text directionality features in TEI files, using the properties and values from the CSS Writing Modes module, encoded in the global TEI @style attribute (or in the TEI <rendition> element and linked with the @rendition attribute). For most texts, it will not be necessary to encode any information about text directionality, either because it follows unambiguously from @xml:lang values, or because it can be expected to be handled unequivocally by the Unicode Bidi Algorithm. Where it is important to encode text directionality, we believe that most phenomena can be well described through the use of the CSS Writing Modes features; of those which cannot, other approaches based on the CSS Transforms module are presented below.

Text transformation

In this section, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the CSS Transforms specification.

We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform:

Here a block of text has been rotated around its z-axis. This is clearly not a "writing mode"; the writing mode for this text is horizontal, left to right. Furthermore, even if we wished to treat this as a writing mode, we could not do so, because there is no way to use writing modes properties to describe an text orientation which is angled at 45 degrees. It is more appropriate to treat this as a rotational transformation. We can do this using two properties: transform and transform-origin. (Both of these properties have quite complex value sets, and we will not look at all of them here. See the specification for full details.)

The transform property takes as its value one or more of the transform functions, one of which is the function rotate:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotate(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>