Difference between revisions of "Text Directionality Draft"

(→Introduction) |

(→Introduction) |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

===Introduction=== | ===Introduction=== | ||

| − | Scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the direction in which these glyphs are to be read. The majority of modern languages are written from left to right within the line, and have their lines stacked from top to bottom vertically (English, Russian, Greek), but there are several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew), while also stacking lines top-to-bottom. East Asian scripts (Sinitic characters, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul, Vietnamese chữ nôm) were traditionally written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left. There are a few cases of bottom-to-top writing, such as Ancient Berber, and some Ogham inscriptions; there are even instances of writing which changes direction on alternate lines (boustrophedon, discussed in detail below). | + | Scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the direction in which these glyphs are to be read. The majority of modern languages are written from left to right within the line, and have their lines stacked from top to bottom vertically (English, Russian, Greek), but there are several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew), while also stacking lines top-to-bottom. East Asian scripts (Sinitic characters, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul, Vietnamese chữ nôm) were traditionally written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left.<ref>Today Chinese in China is printed with the same directionality as English, while printing in Taiwan and Hongkong uses both modes depending on taste and context. The vast majority of books and newpapers in Japanese are printed in the traditional vertical-rl mode, while the lay-out of Korean and Vietnamese is generally ltr / horizontal-tb.</ref> There are a few cases of bottom-to-top writing, such as Ancient Berber, and some Ogham inscriptions; there are even instances of writing which changes direction on alternate lines (boustrophedon, discussed in detail below). |

When a language or script can be arranged in two or more different directions, there are often other consequences arising out of the choice; for example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used, whereas in vertical writing an alternative glyph, U+FE11, may be used to ensure that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. In addition, scripts which normally have a single directionality (such as English) may be written in a different direction in the context of another language (English words inserted into vertical Chinese text, for example), or in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, in which column or row labels may be written vertically to make the most effective use of available space. | When a language or script can be arranged in two or more different directions, there are often other consequences arising out of the choice; for example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used, whereas in vertical writing an alternative glyph, U+FE11, may be used to ensure that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. In addition, scripts which normally have a single directionality (such as English) may be written in a different direction in the context of another language (English words inserted into vertical Chinese text, for example), or in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, in which column or row labels may be written vertically to make the most effective use of available space. | ||

Revision as of 18:19, 29 November 2013

This is a preliminary draft of proposed sections for the TEI Guidelines, created by the Text Directionality Workgroup. Please see the associated Text Directionality Draft Questions document for some issues to think about before and after reading this draft, and feel free to respond there and to add new questions. There is also a talk page for more informal discussion.

Contents

Text directionality and transformation

Introduction

Scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the direction in which these glyphs are to be read. The majority of modern languages are written from left to right within the line, and have their lines stacked from top to bottom vertically (English, Russian, Greek), but there are several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew), while also stacking lines top-to-bottom. East Asian scripts (Sinitic characters, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul, Vietnamese chữ nôm) were traditionally written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left.<ref>Today Chinese in China is printed with the same directionality as English, while printing in Taiwan and Hongkong uses both modes depending on taste and context. The vast majority of books and newpapers in Japanese are printed in the traditional vertical-rl mode, while the lay-out of Korean and Vietnamese is generally ltr / horizontal-tb.</ref> There are a few cases of bottom-to-top writing, such as Ancient Berber, and some Ogham inscriptions; there are even instances of writing which changes direction on alternate lines (boustrophedon, discussed in detail below).

When a language or script can be arranged in two or more different directions, there are often other consequences arising out of the choice; for example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used, whereas in vertical writing an alternative glyph, U+FE11, may be used to ensure that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. In addition, scripts which normally have a single directionality (such as English) may be written in a different direction in the context of another language (English words inserted into vertical Chinese text, for example), or in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, in which column or row labels may be written vertically to make the most effective use of available space.

The directionality features of scripts, and the consequences arising out of them, are generally referred to as "writing modes". For many documents encoded in TEI, there may be no need to encode any information relating to writing mode, because it will be obvious. Modern printed texts in most European languages, for instance, may be expected to use left-to-right/top-to-bottom directionality; Arabic or Hebrew texts are expected to run right-to-left/top-to-bottom. It may appear that directionality can be reliably deduced from the language and script settings, and these are probably already encoded using the @xml:lang attribute in TEI documents (although the W3C i18n Working Group recommends against reliance on language tags for encoding directionality information [per Richard Ishida, W3C; I need to find a formal reference for this]). Even in the case of many "mixed mode" documents (documents in which languages or scripts with different writing modes are mixed together), it may not be necessary to be explicit about directionality. Consider the case of an English text containing a few Arabic words--what is termed a "bidirectional" text:

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

Since Arabic is always written from right to left, we can assume that the Arabic glyphs are to be read in that direction, even if they are in the context of a left-to-right English sentence. In fact, most codepoints in the Unicode standard have a specific directionality setting which helps any rendering engine to determine how they should be ordered. The Latin glyph "a" has a bidirectionality setting of strong left-to-right; the Hebrew א (alef) is strongly right-to-left. Other glyphs have weak or neutral settings because of the contexts in which they may appear. The Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/) provides a complex series of rules enabling user agents to render most mixed-mode texts with predictable and reliable results, based on the bidirectionality class values of their glyphs.

In some mixed-mode texts, though, the Bidirectional Algorithm may not give the desired results. To deal with this, Unicode provides a set of "directional formatting characters" (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/#Directional_Formatting_Codes), also called "bidi formatting code characters", which are additional codepoints whose only function is to signal to a user-agent that a specific directionality setting should be turned on or off. These can be inserted into a text to influence the outcome of the bidirectional algorithm. However, in the case of documents encoded in XML, the W3C explicitly advises that markup rather than directional formatting characters should be used ("In (X)HTML and XML do not use the paired Unicode bidi formatting code characters where equivalent markup is available," http://www.w3.org/International/questions/qa-bidi-controls). We concur with this recommendation, and the remainder of this section and the next provide a set of encoding strategies for handling text directionality without the use of directional formatting characters. The approach we recommend is based on two external specifications, in line with our normal practice of incorporating existing standards where they are available and appropriate. Those specifications are the CSS Writing Modes module (http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css-writing-modes/) and the CSS Transforms module (http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-transforms/). Since (at the time of writing) neither of these modules has yet reached the stage of a Recommendation, the advice offered below should be regarded as provisional, and you should check your usage of the properties concerned against the current version of each specification where possible.

The following sections will present a few simple examples of phenomena relating to text directionality and transformation, along with some suggested encoding strategies based on the following CSS properties from CSS Writing Modes:

direction: ltr | rtl

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

text-orientation: mixed | upright | sideways-right | sideways-left | sideways | use-glyph-orientation<ref>The value "use-glyph-orientation" may be dropped from the CSS Writing Modes specification.</ref>

unicode-bidi: normal | embed | isolate | bidi-override | isolate-override | plaintext

along with the transform property from CSS Transforms.

In the following examples, CSS rules are encoded in the global TEI @style attribute, which applies them directly to the element on which they are specified (and in most cases, its descendants). It is also appropriate, and will often be more efficient, to express the rules in TEI <rendition> elements in the <teiHeader> and point to them using @rendition attributes. It should also be remembered that the CSS specifications are written primarily to guide users providing instructions for the rendering of digital texts, and implementers creating user-agents which will act on these instructions. However, our usage in the context of a TEI document is primarily descriptive rather than prescriptive; we are typically describing the features of a text we are encoding, rather than providing instructions for rendering it. Our purpose below is not to enumerate an exhaustive set of strategies for encoding any writing mode feature you may encounter; rather we will show some simple examples which serve as an introduction to the topic.

Text directionality

Horizontal directionality

Returning to our previous simple example

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

we could use the direction property to make directionality explicit:

direction: ltr | rtl

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">The Arabic term </seg> <seg xml:lang="ar" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">قلم رصاص</seg> <seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">means "pencil".</seg>

</syntaxhighlight>

The use of the direction property is straightforward, but the unicode-bidi property requires some explanation. These three segments are all inline; they form part of a single sentence, although they happen to be encoded on separate lines in this example. The default value for unicode-bidi is "normal", and the CSS Writing Modes specification stipulates that the direction property "has no effect on bidi reordering when specified on inline elements whose unicode-bidi property’s value is normal, because the element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm." In other words, if we want to make it clear that the direction property is effective here, we must include a value for unicode-bidi which will make it so.

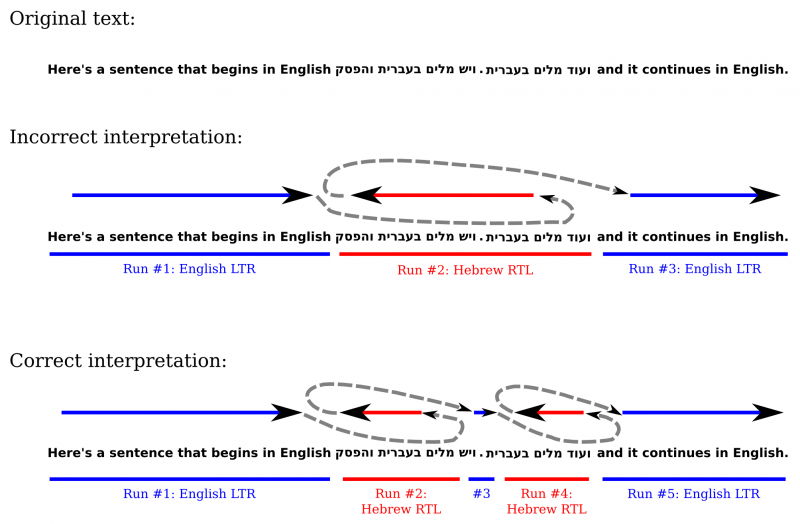

However, as mentioned above, all of the directional encoding in this example is superfluous; ambiguity does not arise in this particular case. Moreover, "ltr" is the default value for the direction property, so we do not need to specify it for the English segments. However, consider the following example, contributed by Efraim Feinstein, in which Hebrew and English text are mixed. (This example is presented in the form of graphics, because we cannot rely on user agents that may be rendering or displaying these Guidelines to provide a consistent output.)

Here, an English period appears in between two runs of Hebrew text. Should that period be interpreted as part of a single run of right-to-left text, or should it be deemed to terminate the first run and precede the second? For the Unicode Bidi Algorithm, punctuation is not strongly directional; it inherits directionality from the surrounding characters. Without further clues, therefore, it would interpret the example as a sequence of three runs (English, Hebrew, English), and arrive at an incorrect interpretation. A clear and correct interpretation requires that not only that the glyphs themselves be transcribed in the correct logical order, but that the encoding eliminate potential ambiguity by delimiting the two Hebrew runs separately, like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

Here's a sentence that begins in English <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: isolate; direction: rtl">ויש מלים בעברית והפסק</seg>. <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: isolate; direction: rtl">ועוד מלים בעברית</seg> and it continues in English.

</syntaxhighlight>

Here the English is unmarked for directionality, but the period is clearly not included in either of the RTL runs, so the ambiguity inherent in the plain text is avoided. Once again, we might argue that the @xml:lang attribute should provide enough information; the important component here is the explicit delimitation of two distinct RTL runs. But additional clarity in the encoding certainly does no harm.

[Would it be helpful to have another example presenting ambiguity arising out of the use of a g element at the end of a text run?]

Vertical writing modes

So far, we have looked only at left-to-right and right-to-left text running horizontally, using the direction: ltr|rtl property. However, there are many scripts and languages which are written vertically (mostly top-to-bottom, but with a few unusal examples running bottom-to-top, as we shall see below). Handling vertical directionality requires the use of another CSS property, the writing mode:

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

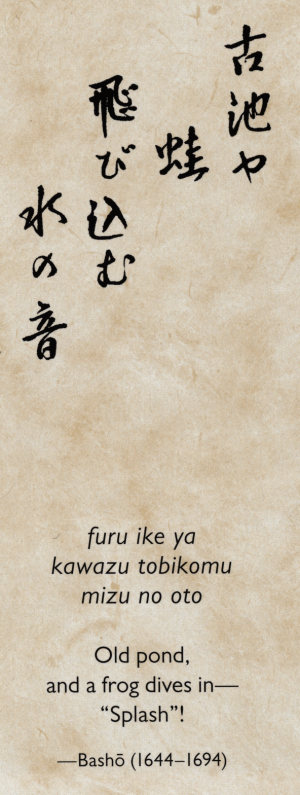

The values for this property include two components: "horizontal" or "vertical" specifies the inline writing direction, while the second component specifies the direction in which lines in a block, and blocks in a sequence may be arranged: from top to bottom (as in most European languages, in which lines and paragraphs are arranged from top to bottom on a page), from right to left (as in the case of some East Asian languages such as Japanese, which we will see below), or left-to-right (e.g. Mongolian). This example shows a Japanese haiku poem transcribed first in Japanese, then in Romaji (Japanese in Latin script), and finally in an English translation.

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_jp" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_romaji #furu-ike-ya_en">

古池や<lb/>

蛙<lb/>

飛び込む<lb/>

水の音

</ab>

<lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_romaji" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_en">

<l>furu ike ya</l>

<l>kawazu tobikomu</l>

<l>mizu no oto</l>

</lg>

<lg xml:lang="en"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_en" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_romaji">

<l>Old pond,</l>

<l>and a frog dives in—</l>

<l>"Splash"!</l>

</lg>

<bibl>—Bashō (1644–1694)</bibl>

</syntaxhighlight>

Note: for the sake of simplicity, the indenting of lines in the vertical Japanese and the central alignment of the other components have been ignored in this encoding, since this section focuses on language and writing mode issues. The Japanese transcription has writing-mode: vertical-rl, which is required because Japanese may be written either in this mode or horizontally. The transcription in Romaji has @xml:lang="ja-Latn" (Japanese written in Latin script) and has a horizontal writing mode; this may seem superfluous, but vertically-written romaji is not unknown.

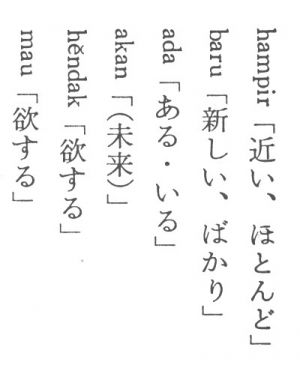

Vertical text with embedded horizontal text

When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters the two orientations; punctuation for instance needs to be positioned differently in vertical versus horizontal text). However, it is very common for languages written vertically to have embedded runs of text from languages normally written horizontally. This raises the issue of the orientation of the glyphs from the horizontal language. Are they written upright, as they would normally appear in horizontal text runs, or are they rotated? Consider this fragment from a Japanese article about the Indonesian language, which takes the form of a glossary list:

This might be transcribed as follows:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja"

style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: mixed"> <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item>

<label xml:lang="id">baru</label> <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item>

</list> </syntaxhighlight>

The rule text-orientation: mixed gives the expected orientation: "In vertical writing modes, characters from horizontal-only scripts are set sideways, i.e. 90° clockwise from their standard orientation in horizontal text. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation" (CSS Writing Modes). In actual fact, the default value for text-orientation is "mixed", so this rule is not strictly required, but if the Indonesian glyphs had been set vertically, like this:

then the encoding would have to be explicit, and we could capture the orientation with text-orientation: upright.

Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts

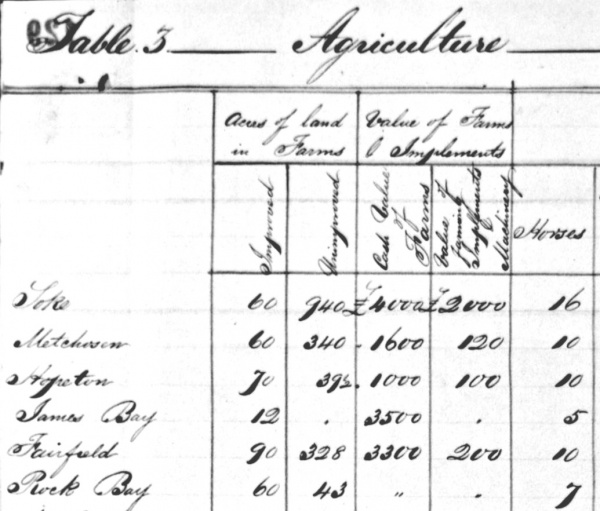

It is not unusual to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where it is not embedded in a text run from a vertically-written script. This example is a fragment from a table of information about agricultural development on Vancouver Island, written in 1855:

Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page. This is not a "native orientation" for English; readers would not find it easy to read this text, and might be inclined to rotate the page in order to read it in a more natural way. To describe this sort of phenomenon, we can use the text-orientation property again:

text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation

For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode one of the four cells containing vertical text like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> Cash Value<lb/> of<lb/> Farms </cell>

</syntaxhighlight>

The writing-mode captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its line/block flow is from left to right (so "of" is to the right of "Cash value"), while the text-orientation value encodes the orientation (rotated 90° counter-clockwise). We might also add text-align: center to the style, to express the fact that the text is centrally-aligned; alignment properties are mapped relative to the line flow, so the word "of" is visibly centred relative to the physical top and bottom of the box, which are the left and right from the point of view of the line flow.

Bottom-to-top writing

There are a very small number of scripts which appear to be written bottom-to-top; perhaps the most well-known is Ogham, an alphabet used mainly to write Archaic Irish. The CSS Writing Modes specification does not explicitly provide for the distinction between top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top in vertically-written scripts; it is argued that all instances of bottom-to-top scripts are actually left-to-right horizontal scripts, oriented vertically because of the constraints of the medium on which they are inscribed (as in the case of Ogham inscriptions on tombstones). In other words, the case of scripts like this is analogous to the vertical English text-runs in the table cells in the example above, and can be handled in exactly the same manner (writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left).

Summary

In this section, we have presented one approach to encoding text directionality features in TEI files, using the properties and values from the CSS Writing Modes module, encoded in the global TEI @style attribute (or in the TEI <rendition> element and linked with the @rendition attribute). For most texts, it will not be necessary to encode any information about text directionality, either because it follows unambiguously from @xml:lang values, or because it can be expected to be handled unequivocally by the Unicode Bidi Algorithm. Where it is important to encode text directionality, we believe that most phenomena can be well described through the use of the CSS Writing Modes features; of those which cannot, other approaches based on the CSS Transforms module are presented below.

Text transformation

Rotation

In what follows, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the CSS Transforms specification. The CSS Transforms module provides a complex array of properties, values and functions which can be used to rotate, skew, translate and otherwise transform textual and graphical objects. We can borrow this vocabulary in order to describe textual phenomena in a precise manner.

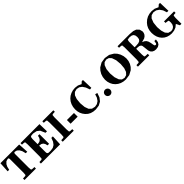

We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform:

Here a block of text has been rotated around its z-axis. This is clearly not a "writing mode"; the writing mode for this text is horizontal, left to right. Furthermore, even if we wished to treat this as a writing mode, we could not do so, because there is no way to use writing modes properties to describe an text orientation which is angled at 45 degrees; no human languages are consistently written in this orientation. It is more appropriate to treat this as a rotational transformation. We can do this using two properties: transform and transform-origin. (Both of these properties have quite complex value sets, and we will not look at all of them here. See the specification for full details.)

The transform property takes as its value one or more of the transform functions, one of which is the function rotateZ:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateZ(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

Any rotation must take place around an axis positioned relative to the element being rotated, and the transform-origin property can be used to specify the pivot point. By default, the value of transform-origin is "50% 50%", the point at the centre of the element, but these values can be changed to reflect rotation around a different origin point. (The TEI zone element also bears an attribute @rotate which can specify rotation in degrees around the z-axis, but it is not available for any other element.)

An element may also be rotated about either of its other axes. For example, this shows rotation around the Y (vertical) axis:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateY(45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

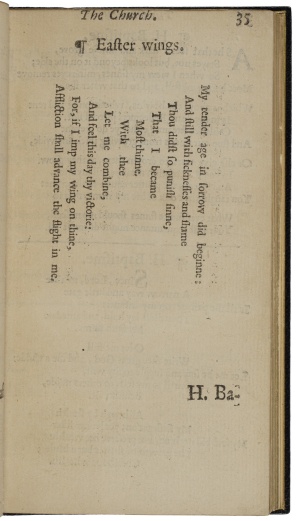

These are obviously trivial examples, but similar features do appear in historical texts. George Herbert's The Temple includes two stanzas headed "Easter Wings" which are both normally printed in a rotated form so that they represent a pair of wings:

This could be encoded thus:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<lg style="transform:rotateX(90deg)"> <l>My tender age in ſorrow did beginne:</l> <l>And ſtill with ſickneſſes and ſhame</l> </lg>

</syntaxhighlight>

but we might also argue that this is in fact a vertical writing mode, and express it with writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: sideways-right.

Boustrophedon

We may also use rotation as a method of handling a true writing mode which is not covered by the CSS Writing Modes: boustrophedon. This is a writing mode common in inscriptions in Latin, Greek and other languages, in which alternate lines run from left to right and from right to left; its name derives from the path of an ox pulling a plough. Right-to-left lines in boustrophedon have another unexpected feature: their glyphs are reversed, so that these lines appear as "mirror writing". This example shows a transcription of a Greek inscription at Dodona:

This might be transcribed as follows (ignoring word boundaries for the moment):

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab> ΗΕΡΜΟΝΤΙΝΑ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΚΑΘΕΟΝΠΟΤΘΕΜ</seg> <lb/> ΕΝΟΣΥΕΝΕΑϜ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΟΙΥΕΝΟΙΤΙΕΚΚ</seg> <lb/> ΡΕΤΑΙΑΣΟΝΑ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΣΙΜΟΣΟΤΤΑΙΕ</seg> <lb/> ΑΣΣΑΙ </ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

The 180-degree rotation around the Y (vertical) axis here gives us exactly the effect of the RTL line in boustrophedon; the order of glyphs is reversed, and so is their individual orientation (in fact, we see them "from the back", as it were). <seg> elements have been used here because these are clearly not "lines" in the sense of poetic lines; the text is continuous prose, and linebreaks are incidental.

There are obviously some unsatisfactory aspects of this manner of encoding boustrophedon. In the inscription above, some words run across linebreaks, so if we wished to tag both words and the right-to-left phenomena, one hierarchy would have to be privileged over the other. By using a transform function rather than a writing mode property, we are apparently suggesting that boustrophedon is not in fact a writing mode, whereas it clearly is. But the CSS Writing Modes specification does not provide support for boustrophedon, because it is a rather obscure historical phenomenon; using a rotational transform is one practical alternative.

Caveats

The effect and behaviour of CSS Transforms properties and values according to the specification are highly dependent on the computed Visual formatting model of an HTML document. TEI currently does not have an explicit processing or formatting model. That is, it is by no means clear whether any given TEI element should be interpreted, for instance, as a block-level or inline-level element; for many elements we may think we can assume block-level (<ab>, "anonymous block") or inline-level (<w>, "word") from the semantics, but even this is risky. As long as the properties and values from the CSS Transforms module are used as a convenient, well-specified descriptive language to capture features of a text, without any expectation of using them directly and reliably for rendering, this is not problematic; we are simply borrowing a useful vocabulary from an external source, and benefiting from the clarity of definition provided by the specification. However, if there is any expectation of using this information to render a text in a predictable and accurate way, it will be essential to provide enough styling information throughout the document hierarchy to resolve all ambiguities with regard to size, positioning, block status, etc. before any element undergoes a transform operation.

<references/>