Difference between revisions of "Text Directionality Draft"

(→Vertical writing modes) |

|||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | This | + | This preliminary draft of proposed sections for the TEI Guidelines, created by the [[Text Directionality Workgroup]] is now (28 April 2014) in the process of being transferred to the TEI svn repository where it will appear as a new section in file Source/Guidelines/en/WD-NonStandardCharacters.xml |

| + | |||

| + | '''Please do not make further changes here.''' | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | See the associated [[Text Directionality Draft Questions]] document for some issues to think about before and after reading this draft, and feel free to respond there and to add new questions. There is also a [[Talk:Text_Directionality_Draft|talk page]] for more informal discussion. | ||

==Text directionality and transformation== | ==Text directionality and transformation== | ||

| − | === | + | ===Writing Modes=== |

| − | + | The scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the way (or ways) that those glyphs are arranged on the writing surface. For the majority of modern languages, writing is arranged as a series of lines which are to be read from top to bottom. Within each line, individual characters are frequently presented from left to right (English, Russian, Greek), but there are also several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew). Writing in which the lines of glyphs are presented vertically and read from right to left is also often encountered, notably in older East Asian scripts (Sinitic characters, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul, Vietnamese chữ nôm). In many cases, a language normally uses the same ''writing mode'' (we use this term to refer to the orientation of individual glyphs within a line and the order in which they should be read), but there are exceptions in which the same language may appear in different modes, for example either vertically or horizontally. East Asian scripts were traditionally written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left. Although modern Japanese, Chinese, and Korean are often written horizontally, the traditional vertical writing mode is still widely used. There are also comparatively rare cases of ancient scripts written with lines running left to right, each line being read top to bottom (Ancient Uighur, classical Mongolian and Manchu), or scripts such as Ogham where the writing direction is from bottom to top around the edge of an inscribed object. | |

| − | When | + | When different languages are combined, it is possible that different writing modes will be needed: for example, in Hebrew text, running right to left, sequences of Latin digits still run left to right. When different writing modes are available for the same language, it may be that different glyphs will be preferred when the script is used in different modes. For example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used in preference to Unicode character U+FE11, the vertical mode comma. This ensures that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. Even for scripts which are usually written in exactly the same way, different writing modes may be encountered in particular contexts; for example when a language using Roman script is embedded within vertically organized Chinese text, it may sometimes be displayed vertically and sometimes horizontally. The writing mode may also vary in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, where column or row labels may be written vertically or diagonally to make the most effective use of available space, just as it may vary in response to the size and shape of the carrier in the case of a monumental inscription. |

| − | + | For many, perhaps most, TEI documents there may be no need to encode the writing mode explicitly, even in so-called "mixed mode" texts containing passages written in languages which use different writing modes. Modern printed texts in most European languages, for instance, may be expected to use left-to-right/top-to-bottom directionality; while Arabic or Hebrew texts are expected to run right-to-left/top-to-bottom. In a TEI document, language and script are explicitly stated in the markup using the attribute xml:lang (reference); this indication will usually imply a particular default writing mode. Even where this attribute is not used, passages in different scripts will use different Unicode characters, and will thus imply a particular default writing mode. | |

| + | |||

| + | Consider the case of an English text containing a few Arabic words : | ||

<code>The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".</code> | <code>The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".</code> | ||

| − | + | A correct TEI encoding might read as follows: | |

| − | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | |

| + | <s xml:lang="en" >The Arabic term | ||

| + | <term xml:lang="ar">قلم رصاص</term> | ||

| + | means "pencil".</s> | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

| + | We might assume that it is the presence of the xml:lang attribute with value "ar" that causes processing software to display the Arabic from right to left, but in fact, this is not the case. The order in which the Arabic characters appear when rendered would be the same, even if the markup were not present: | ||

| − | The | + | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> |

| + | <s>The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".</s> | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is because Arabic glyphs are always displayed right to left, even when they appear within a left-to-right English sentence. Like most other codepoints in the Unicode standard, they have a specific directionality setting which helps any rendering software determine how they should be ordered. The Latin glyph "a" has a strong left-to-right bidirectionality setting, as do the digits 0 to 9; the Hebrew א (alef) is strongly right-to-left. Of course, some glyphs (common punctuation marks such as the period or comma for example) have weak or neutral settings because they may appear in several contexts. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/) defines a number of rules enabling software to render sequences of characters which have differing directionality properties in a predictable and reliable way, using only those properties. <ref>Because this algorithm may not always give the desired result, Unicode also provides a set of "directional formatting characters" (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/#Directional_Formatting_Codes). These additional codepoints can be used to signal to rendering software that a specific directionality setting should be turned on or off. However, in the case of documents encoded in XML, there is no need to use such characters, and in fact the W3C explicitly advises against it. "In (X)HTML and XML do not use the paired Unicode bidi formatting code characters where equivalent markup is available." (http://www.w3.org/International/questions/qa-bidi-controls)</ref>. It should be remembered however that individual sequences of characters are always stored in a file in the order in which they should be read, irrespective of the order in which the characters making up a sequence should be displayed or rendered. For example, in a RTL language such as Hebrew, the first character in a file will be that which is displayed at the rightmost end of the first line of text. | ||

| + | |||

| + | An encoder wishing to document or to control the order in which sequences of characters in a TEI document are displayed will usually do so by segmenting the text into sequences presented in the desired order and specifying an appropriate language code for each. In situations where this approach may result in ambiguity or lack of precision, or if the encoder wishes to record directional information explicitly in their encoding, we recommend using the global @style attribute to supply detail about the writing mode applicable to the content of any element. The @style attribute (discussed in section [ref to #STGAre here] ) permits use of any formatting language; for these purposes however, we recommend use of CSS, which now includes a Writing Modes module <ref>At the time of writing, this W3C module has the status of a candidate recommendation: see further http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css-writing-modes/ </ref> which permits direct specification of a number of useful properties associated with writing modes, notably : | ||

<code> | <code> | ||

| Line 26: | Line 48: | ||

</code> | </code> | ||

| − | + | The global TEI @style attribute applies to the element on which it is specified (and in most cases, its descendants). Rather than specify it on every element, it will often be more efficient, to express sets of commonly-used styling rules as <rendition> elements in the <teiHeader> and then point to them using the global @rendition attribute (see further the discussion in [ref to #HD57-1 here]). Although the CSS specifications are mainly used to provide instructions for software when rendering a digital text, they also provide a useful means of describing the visual properties of a pre-existing document in a formal and standardized way. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the next section, we present some examples of how CSS can be used to describe a variety of writing modes. A full description of the appearance of a document will probably include many other properties of course. | |

| − | === | + | ===Examples=== |

| − | + | The CSS recommendations provides several properties which can be used to encode aspects of the "writing mode". The most useful of these is the property "writing-mode" which may be used to specify a reading-order for both characters within a single line and lines within a single block of text. The property "text-orientation" may also used to indicate the orientation of individual characters with respect to the line, and the property "direction" to determine the reading order of characters within a line only. We give some examples of each below. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Vertical writing modes==== | ====Vertical writing modes==== | ||

| − | + | The writing-mode property is particularly useful for languages which can be written in different writing modes, such as Chinese and Japanese. It has the following possible values: | |

<code>writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr</code> | <code>writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr</code> | ||

| − | + | Each value has two components: "horizontal" or "vertical" specifies the inline writing direction, while the second component specifies the direction in which lines in a block, and blocks in a sequence are arranged: from top to bottom (as in most European languages, in which lines and paragraphs are arranged from top to bottom on a page), from right to left (as in the case of Japanese), or left-to-right (as in the case of Mongolian). | |

| + | |||

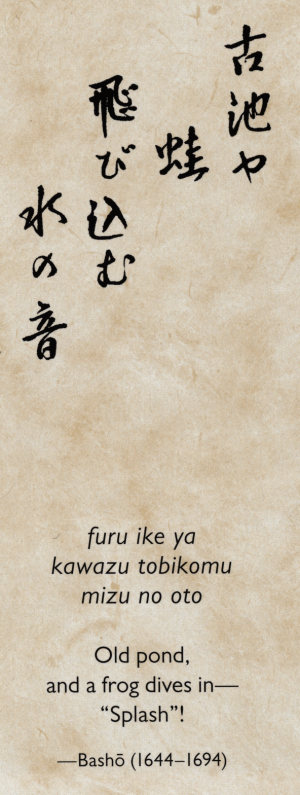

| + | The following example shows three versions of the same poem: first in Japanese, written top to bottom; next in Romaji (Japanese in Latin script); and finally in an English translation. | ||

[[File:Basho_furu_ike_ya.png|thumb|left|alt=Basho poem|Taken from p.42 of ''Haiku: Japanese Art and Poetry''. Judith Patt, Michiko Warkentyne (calligraphy) and Barry Till. 2010. Used with permission.]] | [[File:Basho_furu_ike_ya.png|thumb|left|alt=Basho poem|Taken from p.42 of ''Haiku: Japanese Art and Poetry''. Judith Patt, Michiko Warkentyne (calligraphy) and Barry Till. 2010. Used with permission.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | We might encode this as follows: | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

<div> | <div> | ||

| − | <lg xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl | + | <lg xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl"> |

| − | |||

<l>古池や</l> | <l>古池や</l> | ||

<l>蛙</l>> | <l>蛙</l>> | ||

| Line 89: | Line 80: | ||

</lg> | </lg> | ||

| − | <lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb | + | <lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb"> |

| − | |||

<l>furu ike ya</l> | <l>furu ike ya</l> | ||

<l>kawazu tobikomu</l> | <l>kawazu tobikomu</l> | ||

| Line 96: | Line 86: | ||

</lg> | </lg> | ||

| − | <lg xml:lang="en | + | <lg xml:lang="en"> |

| − | |||

<l>Old pond,</l> | <l>Old pond,</l> | ||

<l>and a frog dives in—</l> | <l>and a frog dives in—</l> | ||

| Line 107: | Line 96: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| − | + | ||

| + | For the sake of simplicity, we have not attempted to capture in this encoding such aspects as the indenting of lines in the first Japanese version, or the central alignment of the other two versions, nor any other renditional features such as font weight or size etc. The Japanese transcription has <code>writing-mode: vertical-rl</code>, which is required because Japanese may be written either in this mode or horizontally. The transcription in Romaji has <code>@xml:lang="ja-Latn"</code> (Japanese written in Latin script) and has a horizontal writing mode; this may seem superfluous, but vertically-written romaji is not unknown. | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

| Line 113: | Line 103: | ||

====Vertical text with embedded horizontal text==== | ====Vertical text with embedded horizontal text==== | ||

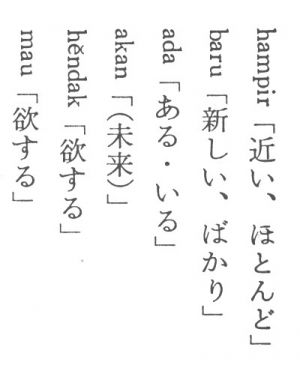

| − | When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters | + | When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters, in particular for punctuation which needs to be positioned differently in vertical and in horizontal text). However, it is very common for languages written vertically to have embedded runs of text from languages which are normally written horizontally. This raises the issue of the orientation of the glyphs from the horizontal language. Are they written upright, as they would normally appear in horizontal text runs, or are they rotated? Consider this fragment from a Japanese article about the Indonesian language, which takes the form of a glossary list: |

[[File:Ja vertical indonesian frag sm.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Glossary list|Taken from p.62 of "インドネシア語". 崎山理. 1985. ''外国語との対照II''. 講座日本語学 11.]] | [[File:Ja vertical indonesian frag sm.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Glossary list|Taken from p.62 of "インドネシア語". 崎山理. 1985. ''外国語との対照II''. 講座日本語学 11.]] | ||

| − | + | The text-orientation property allows us to indicate whether or not glyphs are rotated. In the following example, we have indicated that the list uses a vertical-rl writing mode, but that the orientation of individual glyphs may vary: | |

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

| Line 133: | Line 123: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| − | The rule <code>text-orientation: mixed</code> | + | The rule <code>text-orientation: mixed</code> specifies that "characters from horizontal-only scripts are set sideways, i.e. 90° clockwise from their standard orientation in horizontal text. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation" ([http://www.w3.org/TR/2013/WD-css-writing-modes-3-20131024/#text-orientation CSS Writing Modes]). Since the default value for <code>text-orientation</code> is "mixed", this rule is not strictly required. However, if the Indonesian glyphs (which are roman characters) had been set vertically, like this: |

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

| Line 139: | Line 129: | ||

[[File:Ja vertical indonesian frag rotated sm.jpg|50px|thumb|left|alt=Glossary list|Fragment of previous image with Indonesian glyphs upright.]] | [[File:Ja vertical indonesian frag rotated sm.jpg|50px|thumb|left|alt=Glossary list|Fragment of previous image with Indonesian glyphs upright.]] | ||

| − | then the | + | then an encoding like the following could be used to make this explicit: |

| + | |||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

| + | <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja" | ||

| + | style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: upright"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> | ||

| + | <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <label xml:lang="id">baru</label> | ||

| + | <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- ... --> | ||

| + | </list> | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The rule <code>text-orientation: upright</code> specifies that "characters from horizontal-only scripts are rendered upright, i.e. in their standard horizontal orientation. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation and shaped normally" ([http://www.w3.org/TR/2013/WD-css-writing-modes-3-20131024/#text-orientation CSS Writing Modes]). | ||

<div style="clear: both"> </div> | <div style="clear: both"> </div> | ||

| Line 145: | Line 151: | ||

====Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts==== | ====Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts==== | ||

| − | It is not unusual to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where | + | It is not unusual to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where no vertically-written script is involved. This example is a fragment from a table of information about agricultural development on Vancouver Island, written in 1855: |

[[File:bcgenesis co 305 06 00131v table extract.jpg|thumb|center|600px|alt=Agricultural report table|Enclosure with 10048, CO 305/6, p. 109 http://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/getDoc.htm?id=V55116.scx]] | [[File:bcgenesis co 305 06 00131v table extract.jpg|thumb|center|600px|alt=Agricultural report table|Enclosure with 10048, CO 305/6, p. 109 http://bcgenesis.uvic.ca/getDoc.htm?id=V55116.scx]] | ||

| − | Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page | + | Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page. To describe this sort of phenomenon, we can use the text-orientation property again: |

<code>text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation</code> | <code>text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation</code> | ||

| − | For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode | + | For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode the third of the four cells containing vertical text like this: |

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

<cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> | <cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> | ||

| − | Cash Value<lb/> | + | <lb/>Cash Value |

| − | + | <lb/>of | |

| − | + | <lb/>Farms | |

</cell> | </cell> | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| − | The <code>writing-mode</code> captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its | + | The <code>writing-mode</code> captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its lines are to be read from left to right (so the line containing "of" is to the right of that containing "Cash value"), while the <code>text-orientation</code> value encodes the orientation (rotated 90° counter-clockwise). We might also add <code>text-align: center</code> to the style, to express the fact that the text is centrally-aligned. |

====Bottom-to-top writing==== | ====Bottom-to-top writing==== | ||

| + | Of the rather small number of scripts which appear to be written bottom-to-top, perhaps the most well-known is Ogham, an alphabet used mainly to write Archaic Irish. The CSS Writing Modes specification does not explicitly provide for the distinction between top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top in vertically-written scripts; it is argued that all instances of bottom-to-top scripts are actually left-to-right horizontal scripts, oriented vertically because of the constraints of the medium on which they are inscribed (as in the case of Ogham inscriptions on tombstones). In other words, the case of scripts like this is analogous to the vertical English text-runs in the table cells in the example above, and can be handled in exactly the same manner (<code>writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left</code>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [can't we find an Ogham example? ] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ====Horizontal directionality==== | ||

| + | |||

| + | [Question MDH to LB: Why is this bit detached from the original horizontal text section above? Because he section above isn't specifically about horizontal texts only, though it uses one as an initial example] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Returning to our previous simple example | ||

| + | |||

| + | <code>The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".</code> | ||

| + | |||

| + | we could use the <code>direction</code> property to make directionality explicit: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <code>direction: ltr | rtl</code> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

| + | <s xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">The Arabic term | ||

| + | <term xml:lang="ar" style="direction: rtl; unicode-bidi: embed">قلم رصاص</term> | ||

| + | means "pencil".</s> | ||

| + | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The use of the <code>direction</code> property to record the observed directionality of the text is unambiguous, even though it is (as we noted above) superfluous. <ref>The use of the <code>unicode-bidi</code> property here may require some explanation. By default this property has the value "normal", the effect of which in this context would be to ignore any value supplied for the <code>direction</code> property. The CSS Writing Modes specification stipulates that the <code>direction</code> property "has no effect on bidi reordering when specified on inline elements whose unicode-bidi property’s value is normal, because the element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm."</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Mixed directionality is very common in languages such as Arabic and Hebrew, particularly when numbers (which are always given LTR) or phrases from other LTR languages are embedded, and it is quite unusual though not impossible for ambiguities to arise. | ||

| − | + | [Would it be helpful to have another example presenting ambiguity arising out of the use of a g element at the end of a text run?] [how might a <g> element introduce ambiguity? only if the glyph or character concerned is vague about its directionality surely] [(MDH) A <g> element would normally be used for a glyph which has no Unicode representation; therefore it has no directionality per the Unicode character database; therefore its effect would be potentially disruptive. Imagine a case where a rtl text run ends with a weak-directionality character such as a period, followed by a <g> for a glyph which the encoder knows should represent an rtl character, but which isn't in Unicode, followed by a strongly ltr character.] [If the encoder knows that the glyph or character concerned has a strongly ltr character then they should use the <charProp> element to document this fact within the <glyph> or <char> definition, as per http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/WD.html#ucsprops. If they want a rendering agent to deal with the character properly, they are at liberty to put a strongly ltr character as content for the <g> ] | |

====Summary==== | ====Summary==== | ||

| Line 177: | Line 208: | ||

====Rotation==== | ====Rotation==== | ||

| − | In what follows, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the [http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-transforms/ CSS Transforms] specification. | + | In what follows, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the [http://www.w3.org/TR/css3-transforms/ CSS Transforms] specification. This CSS module provides a complex array of properties, values and functions which can be used to rotate, skew, translate and otherwise transform textual and graphical objects. We can borrow this vocabulary in order to describe textual phenomena in a precise manner. |

We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform: | We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform: | ||

| Line 193: | Line 224: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| − | Any rotation must take place around an axis positioned relative to the element being rotated, and the <code>transform-origin</code> property can be used to specify the pivot point. By default, the value of <code>transform-origin</code> is "50% 50%", the point at the centre of the element, but these values can be changed to reflect rotation around a different origin point. (The TEI [http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/ref-zone.html zone element] also bears an attribute @rotate which can specify rotation in degrees around the z-axis, but it is not available for any other element.) | + | Any rotation must take place clockwise around an axis positioned relative to the element being rotated, and the <code>transform-origin</code> property can be used to specify the pivot point. By default, the value of <code>transform-origin</code> is "50% 50%", the point at the centre of the element, but these values can be changed to reflect rotation around a different origin point. (The TEI [http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/ref-zone.html zone element] also bears an attribute @rotate which can specify rotation in degrees around the z-axis, but it is not available for any other element.) |

An element may also be rotated about either of its other axes. For example, this shows rotation around the Y (vertical) axis: | An element may also be rotated about either of its other axes. For example, this shows rotation around the Y (vertical) axis: | ||

| Line 219: | Line 250: | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| − | + | We might also argue that this is in fact a vertical writing mode, and express it with <code>writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: sideways-right</code>. | |

<div style="clear: both;"> </div> | <div style="clear: both;"> </div> | ||

| Line 233: | Line 264: | ||

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | <syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> | ||

<ab> | <ab> | ||

| − | + | <lb/>ΗΕΡΜΟΝΤΙΝA | |

| − | + | <lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΚΑΘΕΟΝΠΟΤΘΕΜ</seg> | |

| − | + | <lb/>ΕΝΟΣΥΕΝΕΑϜ | |

| − | + | <lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΟΙΥΕΝΟΙΤΙΕΚΚ</seg> | |

| − | + | <lb/>ΡΕΤΑΙΑΣΟΝΑ | |

| − | + | <lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΣΙΜΟΣΟΤΤΑΙΕ</seg> | |

| − | + | <lb/>ΑΣΣΑΙ | |

</ab> | </ab> | ||

</syntaxhighlight> | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

| Line 251: | Line 282: | ||

====Caveats==== | ====Caveats==== | ||

| − | + | As with other parts of the CSS specification, the intended effect of CSS Transforms properties and values are defined with reference to a specific [http://www.w3.org/TR/CSS2/visuren.html Visual formatting model]; the language is designed to describe how an HTML document should be formatted. This is not, of course, the case for the TEI, which lacks any explicit processing or formatting model, and attempts to define objects as far as possible without consideration of their visual appearance. As long as the properties and values from the CSS Transforms module are used as a convenient, well-specified descriptive language to capture features of a text, without any expectation of using them directly and reliably for rendering, this is not particularly problematic. CSS provides a useful and well-defined vocabulary to describe many aspects of the appearance of source texts, benefitting particularly from the clarity of definition provided by the specification. However, if there is any expectation of using this information to render a text in a predictable and accurate way, it will be essential to provide enough styling information throughout the document hierarchy to resolve all ambiguities with regard to size, positioning, block status, etc. before any element undergoes a transform operation. | |

<references/> | <references/> | ||

Latest revision as of 13:47, 28 April 2014

This preliminary draft of proposed sections for the TEI Guidelines, created by the Text Directionality Workgroup is now (28 April 2014) in the process of being transferred to the TEI svn repository where it will appear as a new section in file Source/Guidelines/en/WD-NonStandardCharacters.xml

Please do not make further changes here.

See the associated Text Directionality Draft Questions document for some issues to think about before and after reading this draft, and feel free to respond there and to add new questions. There is also a talk page for more informal discussion.

Contents

Text directionality and transformation

Writing Modes

The scripts used for writing human languages vary not only in the glyphs they use, but also in the way (or ways) that those glyphs are arranged on the writing surface. For the majority of modern languages, writing is arranged as a series of lines which are to be read from top to bottom. Within each line, individual characters are frequently presented from left to right (English, Russian, Greek), but there are also several widely-used scripts which run right-to-left (Arabic, Hebrew). Writing in which the lines of glyphs are presented vertically and read from right to left is also often encountered, notably in older East Asian scripts (Sinitic characters, Japanese Kana, Korean Hangul, Vietnamese chữ nôm). In many cases, a language normally uses the same writing mode (we use this term to refer to the orientation of individual glyphs within a line and the order in which they should be read), but there are exceptions in which the same language may appear in different modes, for example either vertically or horizontally. East Asian scripts were traditionally written from top to bottom within the line, with their lines sequenced from right to left. Although modern Japanese, Chinese, and Korean are often written horizontally, the traditional vertical writing mode is still widely used. There are also comparatively rare cases of ancient scripts written with lines running left to right, each line being read top to bottom (Ancient Uighur, classical Mongolian and Manchu), or scripts such as Ogham where the writing direction is from bottom to top around the edge of an inscribed object.

When different languages are combined, it is possible that different writing modes will be needed: for example, in Hebrew text, running right to left, sequences of Latin digits still run left to right. When different writing modes are available for the same language, it may be that different glyphs will be preferred when the script is used in different modes. For example, when Japanese is written horizontally, the Unicode character U+3001, the "ideographic comma", is used in preference to Unicode character U+FE11, the vertical mode comma. This ensures that the comma appears in the correct position relative to the surrounding glyphs. Even for scripts which are usually written in exactly the same way, different writing modes may be encountered in particular contexts; for example when a language using Roman script is embedded within vertically organized Chinese text, it may sometimes be displayed vertically and sometimes horizontally. The writing mode may also vary in response to layout constraints such as those imposed by a complex table, where column or row labels may be written vertically or diagonally to make the most effective use of available space, just as it may vary in response to the size and shape of the carrier in the case of a monumental inscription.

For many, perhaps most, TEI documents there may be no need to encode the writing mode explicitly, even in so-called "mixed mode" texts containing passages written in languages which use different writing modes. Modern printed texts in most European languages, for instance, may be expected to use left-to-right/top-to-bottom directionality; while Arabic or Hebrew texts are expected to run right-to-left/top-to-bottom. In a TEI document, language and script are explicitly stated in the markup using the attribute xml:lang (reference); this indication will usually imply a particular default writing mode. Even where this attribute is not used, passages in different scripts will use different Unicode characters, and will thus imply a particular default writing mode.

Consider the case of an English text containing a few Arabic words :

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

A correct TEI encoding might read as follows:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

The Arabic term <term xml:lang="ar">قلم رصاص</term> means "pencil".

</syntaxhighlight>

We might assume that it is the presence of the xml:lang attribute with value "ar" that causes processing software to display the Arabic from right to left, but in fact, this is not the case. The order in which the Arabic characters appear when rendered would be the same, even if the markup were not present:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

</syntaxhighlight>

This is because Arabic glyphs are always displayed right to left, even when they appear within a left-to-right English sentence. Like most other codepoints in the Unicode standard, they have a specific directionality setting which helps any rendering software determine how they should be ordered. The Latin glyph "a" has a strong left-to-right bidirectionality setting, as do the digits 0 to 9; the Hebrew א (alef) is strongly right-to-left. Of course, some glyphs (common punctuation marks such as the period or comma for example) have weak or neutral settings because they may appear in several contexts.

The Unicode Bidirectional Algorithm (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/) defines a number of rules enabling software to render sequences of characters which have differing directionality properties in a predictable and reliable way, using only those properties. <ref>Because this algorithm may not always give the desired result, Unicode also provides a set of "directional formatting characters" (http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr9/#Directional_Formatting_Codes). These additional codepoints can be used to signal to rendering software that a specific directionality setting should be turned on or off. However, in the case of documents encoded in XML, there is no need to use such characters, and in fact the W3C explicitly advises against it. "In (X)HTML and XML do not use the paired Unicode bidi formatting code characters where equivalent markup is available." (http://www.w3.org/International/questions/qa-bidi-controls)</ref>. It should be remembered however that individual sequences of characters are always stored in a file in the order in which they should be read, irrespective of the order in which the characters making up a sequence should be displayed or rendered. For example, in a RTL language such as Hebrew, the first character in a file will be that which is displayed at the rightmost end of the first line of text.

An encoder wishing to document or to control the order in which sequences of characters in a TEI document are displayed will usually do so by segmenting the text into sequences presented in the desired order and specifying an appropriate language code for each. In situations where this approach may result in ambiguity or lack of precision, or if the encoder wishes to record directional information explicitly in their encoding, we recommend using the global @style attribute to supply detail about the writing mode applicable to the content of any element. The @style attribute (discussed in section [ref to #STGAre here] ) permits use of any formatting language; for these purposes however, we recommend use of CSS, which now includes a Writing Modes module <ref>At the time of writing, this W3C module has the status of a candidate recommendation: see further http://dev.w3.org/csswg/css-writing-modes/ </ref> which permits direct specification of a number of useful properties associated with writing modes, notably :

direction: ltr | rtl

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

text-orientation: mixed | upright | sideways-right | sideways-left | sideways | use-glyph-orientation<ref>The value "use-glyph-orientation" may be dropped from the CSS Writing Modes specification.</ref>

unicode-bidi: normal | embed | isolate | bidi-override | isolate-override | plaintext

The global TEI @style attribute applies to the element on which it is specified (and in most cases, its descendants). Rather than specify it on every element, it will often be more efficient, to express sets of commonly-used styling rules as <rendition> elements in the <teiHeader> and then point to them using the global @rendition attribute (see further the discussion in [ref to #HD57-1 here]). Although the CSS specifications are mainly used to provide instructions for software when rendering a digital text, they also provide a useful means of describing the visual properties of a pre-existing document in a formal and standardized way.

In the next section, we present some examples of how CSS can be used to describe a variety of writing modes. A full description of the appearance of a document will probably include many other properties of course.

Examples

The CSS recommendations provides several properties which can be used to encode aspects of the "writing mode". The most useful of these is the property "writing-mode" which may be used to specify a reading-order for both characters within a single line and lines within a single block of text. The property "text-orientation" may also used to indicate the orientation of individual characters with respect to the line, and the property "direction" to determine the reading order of characters within a line only. We give some examples of each below.

Vertical writing modes

The writing-mode property is particularly useful for languages which can be written in different writing modes, such as Chinese and Japanese. It has the following possible values:

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

Each value has two components: "horizontal" or "vertical" specifies the inline writing direction, while the second component specifies the direction in which lines in a block, and blocks in a sequence are arranged: from top to bottom (as in most European languages, in which lines and paragraphs are arranged from top to bottom on a page), from right to left (as in the case of Japanese), or left-to-right (as in the case of Mongolian).

The following example shows three versions of the same poem: first in Japanese, written top to bottom; next in Romaji (Japanese in Latin script); and finally in an English translation.

We might encode this as follows:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<lg xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl"> <l>古池や</l> <l>蛙</l>> <l>飛び込む</l> <l>水の音</l> </lg>

<lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb"> <l>furu ike ya</l> <l>kawazu tobikomu</l> <l>mizu no oto</l> </lg>

<lg xml:lang="en"> <l>Old pond,</l> <l>and a frog dives in—</l> <l>"Splash"!</l> </lg>

<bibl>—Bashō (1644–1694)</bibl>

</syntaxhighlight>

For the sake of simplicity, we have not attempted to capture in this encoding such aspects as the indenting of lines in the first Japanese version, or the central alignment of the other two versions, nor any other renditional features such as font weight or size etc. The Japanese transcription has writing-mode: vertical-rl, which is required because Japanese may be written either in this mode or horizontally. The transcription in Romaji has @xml:lang="ja-Latn" (Japanese written in Latin script) and has a horizontal writing mode; this may seem superfluous, but vertically-written romaji is not unknown.

Vertical text with embedded horizontal text

When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters, in particular for punctuation which needs to be positioned differently in vertical and in horizontal text). However, it is very common for languages written vertically to have embedded runs of text from languages which are normally written horizontally. This raises the issue of the orientation of the glyphs from the horizontal language. Are they written upright, as they would normally appear in horizontal text runs, or are they rotated? Consider this fragment from a Japanese article about the Indonesian language, which takes the form of a glossary list:

The text-orientation property allows us to indicate whether or not glyphs are rotated. In the following example, we have indicated that the list uses a vertical-rl writing mode, but that the orientation of individual glyphs may vary:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja"

style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: mixed"> <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item>

<label xml:lang="id">baru</label> <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item>

</list> </syntaxhighlight>

The rule text-orientation: mixed specifies that "characters from horizontal-only scripts are set sideways, i.e. 90° clockwise from their standard orientation in horizontal text. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation" (CSS Writing Modes). Since the default value for text-orientation is "mixed", this rule is not strictly required. However, if the Indonesian glyphs (which are roman characters) had been set vertically, like this:

then an encoding like the following could be used to make this explicit:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja"

style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: upright"> <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item>

<label xml:lang="id">baru</label> <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item>

</list> </syntaxhighlight>

The rule text-orientation: upright specifies that "characters from horizontal-only scripts are rendered upright, i.e. in their standard horizontal orientation. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation and shaped normally" (CSS Writing Modes).

Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts

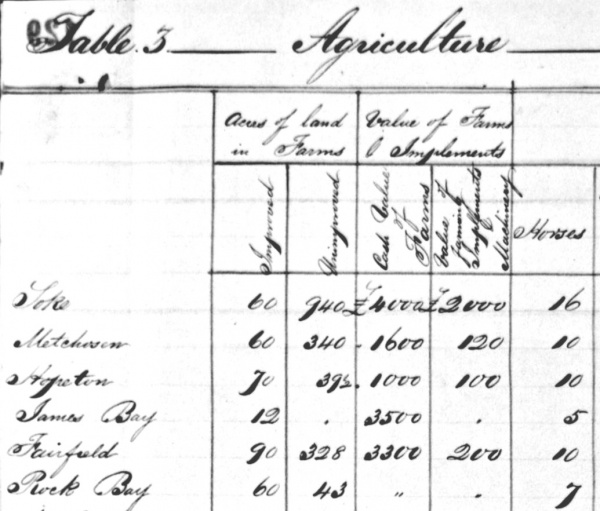

It is not unusual to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where no vertically-written script is involved. This example is a fragment from a table of information about agricultural development on Vancouver Island, written in 1855:

Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page. To describe this sort of phenomenon, we can use the text-orientation property again:

text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation

For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode the third of the four cells containing vertical text like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> <lb/>Cash Value <lb/>of <lb/>Farms </cell>

</syntaxhighlight>

The writing-mode captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its lines are to be read from left to right (so the line containing "of" is to the right of that containing "Cash value"), while the text-orientation value encodes the orientation (rotated 90° counter-clockwise). We might also add text-align: center to the style, to express the fact that the text is centrally-aligned.

Bottom-to-top writing

Of the rather small number of scripts which appear to be written bottom-to-top, perhaps the most well-known is Ogham, an alphabet used mainly to write Archaic Irish. The CSS Writing Modes specification does not explicitly provide for the distinction between top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top in vertically-written scripts; it is argued that all instances of bottom-to-top scripts are actually left-to-right horizontal scripts, oriented vertically because of the constraints of the medium on which they are inscribed (as in the case of Ogham inscriptions on tombstones). In other words, the case of scripts like this is analogous to the vertical English text-runs in the table cells in the example above, and can be handled in exactly the same manner (writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left).

[can't we find an Ogham example? ]

Horizontal directionality

[Question MDH to LB: Why is this bit detached from the original horizontal text section above? Because he section above isn't specifically about horizontal texts only, though it uses one as an initial example]

Returning to our previous simple example

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

we could use the direction property to make directionality explicit:

direction: ltr | rtl

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

The Arabic term <term xml:lang="ar" style="direction: rtl; unicode-bidi: embed">قلم رصاص</term> means "pencil".

</syntaxhighlight>

The use of the direction property to record the observed directionality of the text is unambiguous, even though it is (as we noted above) superfluous. <ref>The use of the unicode-bidi property here may require some explanation. By default this property has the value "normal", the effect of which in this context would be to ignore any value supplied for the direction property. The CSS Writing Modes specification stipulates that the direction property "has no effect on bidi reordering when specified on inline elements whose unicode-bidi property’s value is normal, because the element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm."</ref>

Mixed directionality is very common in languages such as Arabic and Hebrew, particularly when numbers (which are always given LTR) or phrases from other LTR languages are embedded, and it is quite unusual though not impossible for ambiguities to arise.

[Would it be helpful to have another example presenting ambiguity arising out of the use of a g element at the end of a text run?] [how might a <g> element introduce ambiguity? only if the glyph or character concerned is vague about its directionality surely] [(MDH) A <g> element would normally be used for a glyph which has no Unicode representation; therefore it has no directionality per the Unicode character database; therefore its effect would be potentially disruptive. Imagine a case where a rtl text run ends with a weak-directionality character such as a period, followed by a <g> for a glyph which the encoder knows should represent an rtl character, but which isn't in Unicode, followed by a strongly ltr character.] [If the encoder knows that the glyph or character concerned has a strongly ltr character then they should use the <charProp> element to document this fact within the <glyph> or <char> definition, as per http://www.tei-c.org/release/doc/tei-p5-doc/en/html/WD.html#ucsprops. If they want a rendering agent to deal with the character properly, they are at liberty to put a strongly ltr character as content for the <g> ]

Summary

In this section, we have presented one approach to encoding text directionality features in TEI files, using the properties and values from the CSS Writing Modes module, encoded in the global TEI @style attribute (or in the TEI <rendition> element and linked with the @rendition attribute). For most texts, it will not be necessary to encode any information about text directionality, either because it follows unambiguously from @xml:lang values, or because it can be expected to be handled unequivocally by the Unicode Bidi Algorithm. Where it is important to encode text directionality, we believe that most phenomena can be well described through the use of the CSS Writing Modes features; of those which cannot, other approaches based on the CSS Transforms module are presented below.

Text transformation

Rotation

In what follows, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the CSS Transforms specification. This CSS module provides a complex array of properties, values and functions which can be used to rotate, skew, translate and otherwise transform textual and graphical objects. We can borrow this vocabulary in order to describe textual phenomena in a precise manner.

We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform:

Here a block of text has been rotated around its z-axis. This is clearly not a "writing mode"; the writing mode for this text is horizontal, left to right. Furthermore, even if we wished to treat this as a writing mode, we could not do so, because there is no way to use writing modes properties to describe an text orientation which is angled at 45 degrees; no human languages are consistently written in this orientation. It is more appropriate to treat this as a rotational transformation. We can do this using two properties: transform and transform-origin. (Both of these properties have quite complex value sets, and we will not look at all of them here. See the specification for full details.)

The transform property takes as its value one or more of the transform functions, one of which is the function rotateZ:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateZ(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

Any rotation must take place clockwise around an axis positioned relative to the element being rotated, and the transform-origin property can be used to specify the pivot point. By default, the value of transform-origin is "50% 50%", the point at the centre of the element, but these values can be changed to reflect rotation around a different origin point. (The TEI zone element also bears an attribute @rotate which can specify rotation in degrees around the z-axis, but it is not available for any other element.)

An element may also be rotated about either of its other axes. For example, this shows rotation around the Y (vertical) axis:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateY(45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

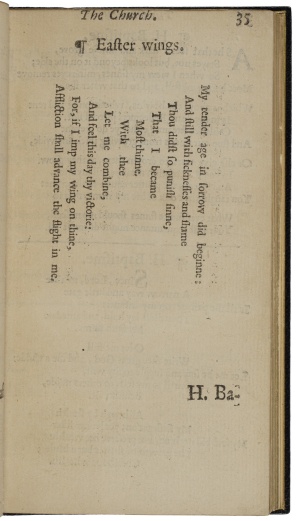

These are obviously trivial examples, but similar features do appear in historical texts. George Herbert's The Temple includes two stanzas headed "Easter Wings" which are both normally printed in a rotated form so that they represent a pair of wings:

This could be encoded thus:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<lg style="transform:rotateZ(90deg)"> <l>My tender age in ſorrow did beginne:</l> <l>And ſtill with ſickneſſes and ſhame</l> </lg>

</syntaxhighlight>

We might also argue that this is in fact a vertical writing mode, and express it with writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: sideways-right.

Boustrophedon

We may also use rotation as a method of handling a true writing mode which is not covered by the CSS Writing Modes: boustrophedon. This is a writing mode common in inscriptions in Latin, Greek and other languages, in which alternate lines run from left to right and from right to left; its name derives from the path of an ox pulling a plough. Right-to-left lines in boustrophedon have another unexpected feature: their glyphs are reversed, so that these lines appear as "mirror writing". This example shows a transcription of a Greek inscription at Dodona:

This might be transcribed as follows (ignoring word boundaries for the moment):

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab>

<lb/>ΗΕΡΜΟΝΤΙΝA

<lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΚΑΘΕΟΝΠΟΤΘΕΜ</seg>

<lb/>ΕΝΟΣΥΕΝΕΑϜ

<lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΟΙΥΕΝΟΙΤΙΕΚΚ</seg>

<lb/>ΡΕΤΑΙΑΣΟΝΑ

<lb/><seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΣΙΜΟΣΟΤΤΑΙΕ</seg>

<lb/>ΑΣΣΑΙ

</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

The 180-degree rotation around the Y (vertical) axis here gives us exactly the effect of the RTL line in boustrophedon; the order of glyphs is reversed, and so is their individual orientation (in fact, we see them "from the back", as it were). <seg> elements have been used here because these are clearly not "lines" in the sense of poetic lines; the text is continuous prose, and linebreaks are incidental.

There are obviously some unsatisfactory aspects of this manner of encoding boustrophedon. In the inscription above, some words run across linebreaks, so if we wished to tag both words and the right-to-left phenomena, one hierarchy would have to be privileged over the other. By using a transform function rather than a writing mode property, we are apparently suggesting that boustrophedon is not in fact a writing mode, whereas it clearly is. But the CSS Writing Modes specification does not provide support for boustrophedon, because it is a rather obscure historical phenomenon; using a rotational transform is one practical alternative.

Caveats

As with other parts of the CSS specification, the intended effect of CSS Transforms properties and values are defined with reference to a specific Visual formatting model; the language is designed to describe how an HTML document should be formatted. This is not, of course, the case for the TEI, which lacks any explicit processing or formatting model, and attempts to define objects as far as possible without consideration of their visual appearance. As long as the properties and values from the CSS Transforms module are used as a convenient, well-specified descriptive language to capture features of a text, without any expectation of using them directly and reliably for rendering, this is not particularly problematic. CSS provides a useful and well-defined vocabulary to describe many aspects of the appearance of source texts, benefitting particularly from the clarity of definition provided by the specification. However, if there is any expectation of using this information to render a text in a predictable and accurate way, it will be essential to provide enough styling information throughout the document hierarchy to resolve all ambiguities with regard to size, positioning, block status, etc. before any element undergoes a transform operation.

<references/>