Difference between revisions of "Text Directionality Draft"

(→Introduction) |

(→Introduction) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

===Text directionality=== | ===Text directionality=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

====Horizontal directionality==== | ====Horizontal directionality==== | ||

Revision as of 01:31, 3 November 2013

This is a preliminary draft of proposed sections for the TEI Guidelines, created by the Text Directionality Workgroup.

Text directionality and transformation

Text directionality

Horizontal directionality

Returning to our previous simple example

The Arabic term قلم رصاص means "pencil".

we could use the direction property to make directionality explicit:

direction: ltr | rtl

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">The Arabic term </seg> <seg xml:lang="ar" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">قلم رصاص</seg> <seg xml:lang="en" style="direction: ltr">means "pencil".</seg>

</syntaxhighlight>

The use of the direction property is straightforward, but the unicode-bidi property requires some explanation. These three segments are all inline; they form part of a single sentence, although they happen to be encoded on separate lines in this example. The default value for unicode-bidi is "normal", and the CSS Writing Modes specification stipulates that the direction property "has no effect on bidi reordering when specified on inline elements whose unicode-bidi property’s value is normal, because the element does not open an additional level of embedding with respect to the bidirectional algorithm." In other words, if we want to make it clear that the direction property is effective here, we must include a value for unicode-bidi which will make it so.

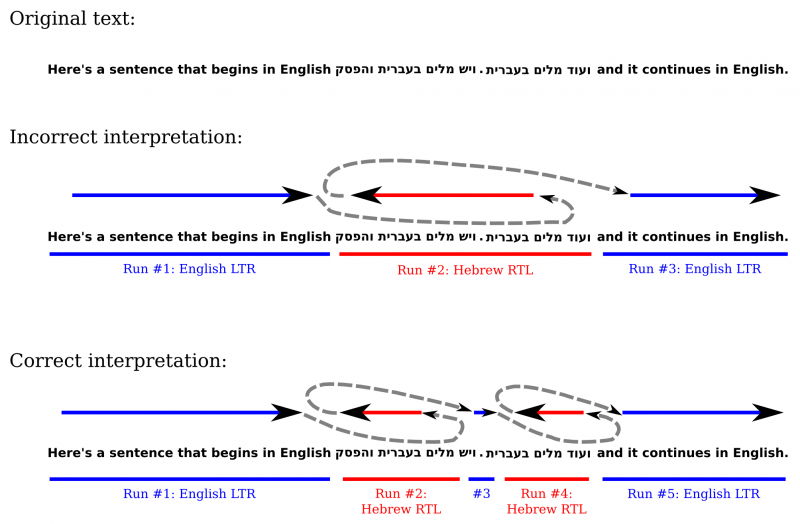

However, as mentioned above, all of the directional encoding in this example is superfluous; ambiguity does not arise in this particular case. Moreover, "ltr" is the default value for the direction property, so we do not need to specify it for the English segments. However, consider the following example, in which Hebrew and English text are mixed. (This example is presented in the form of graphics, because we cannot rely on user agents that may be rendering or displaying these Guidelines to provide a consistent output.)

Here, an English period appears in between two runs of Hebrew text. Should that period be interpreted as part of a single run of right-to-left text, or should it be deemed to terminate the first run and precede the second? For the Unicode Bidi Algorithm, punctuation is not strongly directional; it inherits directionality from the surrounding characters. Without further clues, therefore, it would interpret the example as a sequence of three runs (English, Hebrew, English), and arrive at an incorrect interpretation. A clear and correct interpretation requires that we delimit the two Hebrew runs separately, like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

Here's a sentence that begins in English <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">ויש מלים בעברית והפסק</seg>. <seg xml:lang="he" style="unicode-bidi: embed; direction: rtl">ועוד מלים בעברית</seg> and it continues in English.

</syntaxhighlight>

Here the English is unmarked for directionality, but the period is clearly not included in either of the RTL runs, so the ambiguity inherent in the plain text is avoided. Once again, we might argue that the @xml:lang attribute should provide enough information; the important component here is the explicit delimitation of two distinct RTL runs. But additional clarity in the encoding certainly does no harm.

[Would it be helpful to have another example presenting ambiguity arising out of the use of a g element at the end of a text run?]

Vertical writing modes

So far, we have looked only at left-to-right and right-to-left text running horizontally, using the direction: ltr|rtl property. However, there are many scripts and languages which are written vertically (mostly top-to-bottom, but with a few unusal examples running bottom-to-top, as we shall see below). Handling vertical directionality requires the use of another CSS property, the writing mode:

writing-mode: horizontal-tb | vertical-rl | vertical-lr

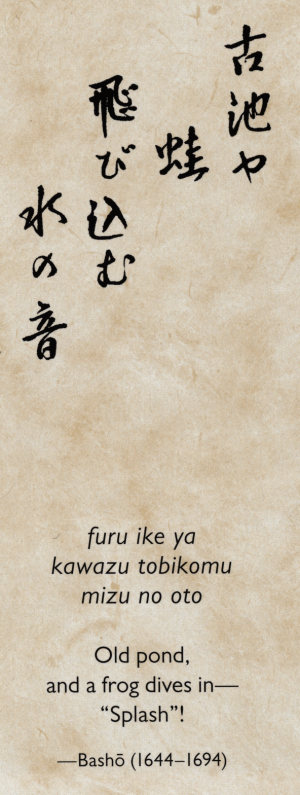

The values for this property include two components: "horizontal" or "vertical" specifies the inline writing direction, while the second component specifies the direction in which lines in a block, and blocks in a sequence may be arranged: from top to bottom (as in most European languages, in which lines and paragraphs are arranged from top to bottom on a page), from right to left (as in the case of some East Asian languages such as Japanese, which we will see below), or left-to-right (e.g. Mongolian). This example shows a Japanese haiku poem transcribed first in Japanese, then in Romaji (Japanese in Latin script), and finally in an English translation.

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab xml:lang="ja" style="writing-mode: vertical-rl"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_jp" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_romaji #furu-ike-ya_en">

古池や<lb/>

蛙<lb/>

飛び込む<lb/>

水の音

</ab>

<lg xml:lang="ja-Latn" style="writing-mode: horizontal-tb"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_romaji" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_en">

<l>furu ike ya</l>

<l>kawazu tobikomu</l>

<l>mizu no oto</l>

</lg>

<lg xml:lang="en"

xml:id="furu-ike-ya_en" corresp="#furu-ike-ya_jp #furu-ike-ya_romaji">

<l>Old pond,</l>

<l>and a frog dives in—</l>

<l>"Splash"!</l>

</lg>

<bibl>—Bashō (1644–1694)</bibl>

</syntaxhighlight>

Note: for the sake of simplicity, the indenting of lines in the vertical Japanese and the central alignment of the other components have been ignored in this encoding, since this section focuses on language and writing mode issues. The Japanese transcription has writing-mode: vertical-rl, which is required because Japanese may be written either in this mode or horizontally. The transcription in Romaji has @xml:lang="ja-Latn" (Japanese written in Latin script) and has a horizontal writing mode; this may seem superfluous, but vertically-written romaji is not unknown.

Vertical text with embedded horizontal text

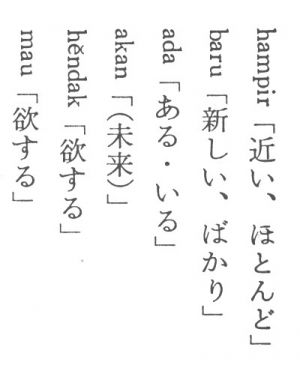

When Japanese is written vertically, the glyph orientation remains the same as when it is written horizontally. In other words, glyphs are not rotated (although as noted above some different glyphs may be used for some characters the two orientations; punctuation for instance needs to be positioned differently in vertical versus horizontal text). However, it is very common for languages written vertically to have embedded runs of text from languages normally written horizontally. This raises the issue of the orientation of the glyphs from the horizontal language. Are they written upright, as they would normally appear in horizontal text runs, or are they rotated? Consider this fragment from a Japanese article about the Indonesian language, which takes the form of a glossary list:

This might be transcribed as follows:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml"> <list type="gloss" xml:lang="ja"

style="writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: mixed"> <label xml:lang="id">hampir</label> <item>「近い、ほとんど」</item>

<label xml:lang="id">baru</label> <item>「新しい、ばかい」</item>

</list> </syntaxhighlight>

The rule text-orientation: mixed gives the expected orientation: "In vertical writing modes, characters from horizontal-only scripts are set sideways, i.e. 90° clockwise from their standard orientation in horizontal text. Characters from vertical scripts are set with their intrinsic orientation" (CSS Writing Modes). In actual fact, the default value for text-orientation is "mixed", so this rule is not strictly required, but if the Indonesian glyphs had been set vertically, like this:

then the encoding would have to be explicit, and we could capture the orientation with text-orientation: upright.

Vertical orientation in horizontal scripts

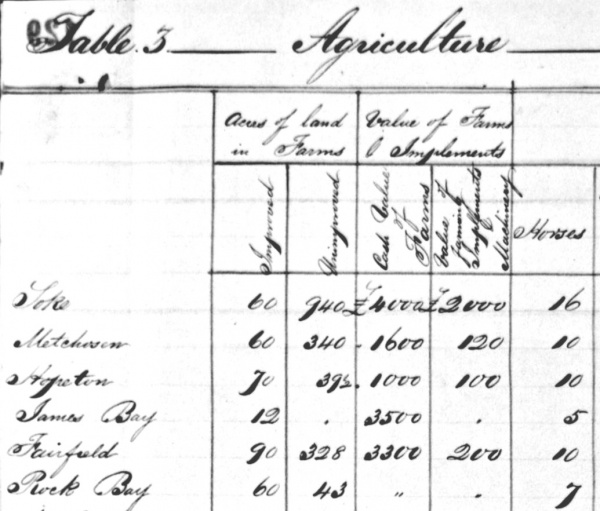

It is not unusual to see text from horizontal languages written vertically even where it is not embedded in a text run from a vertically-written script. This example is a fragment from a table of information about agricultural development on Vancouver Island, written in 1855:

Four subheading cells in this fragment contain English text, written vertically, bottom-to-top, to conserve space on the page. This is not a "native orientation" for English; readers would not find it easy to read this text, and might be inclined to rotate the page in order to read it in a more natural way. To describe this sort of phenomenon, we can use the text-orientation property again:

text-orientation: mixed|upright|sideways-right|sideways-left|sideways|use-glyph-orientation

For full details on this property, we refer the reader to the CSS Writing Modes specification. For the present example, we will make use only of the "sideways-left" value, which "causes text to be set as if in a horizontal layout, but rotated 90° counter-clockwise." We might encode one of the four cells containing vertical text like this:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<cell style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left"> Cash Value<lb/> of<lb/> Farms </cell>

</syntaxhighlight>

The writing-mode captures the fact that the script is written vertically, and its line/block flow is from left to right (so "of" is to the right of "Cash value"), while the text-orientation value encodes the orientation (rotated 90° counter-clockwise). We might also add text-align: center to the style, to express the fact that the text is centrally-aligned; alignment properties are mapped relative to the line flow, so the word "of" is visibly centred relative to the physical top and bottom of the box, which are the left and right from the point of view of the line flow.

Bottom-to-top writing

There are a very small number of scripts which appear to be written bottom-to-top; perhaps the most well-known is Ogham, an alphabet used mainly to write Archaic Irish. The CSS Writing Modes specification does not explicitly provide for the distinction between top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top in vertically-written scripts; it is argued that all instances of bottom-to-top scripts are actually left-to-right horizontal scripts, oriented vertically because of the constraints of the medium on which they are inscribed (as in the case of Ogham inscriptions on tombstones). In other words, the case of scripts like this is analogous to the vertical English text-runs in the table cells in the example above, and can be handled in exactly the same manner (writing-mode: vertical-lr; text-orientation: sideways-left).

Summary

In this section, we have presented one approach to encoding text directionality features in TEI files, using the properties and values from the CSS Writing Modes module, encoded in the global TEI @style attribute (or in the TEI <rendition> element and linked with the @rendition attribute). For most texts, it will not be necessary to encode any information about text directionality, either because it follows unambiguously from @xml:lang values, or because it can be expected to be handled unequivocally by the Unicode Bidi Algorithm. Where it is important to encode text directionality, we believe that most phenomena can be well described through the use of the CSS Writing Modes features; of those which cannot, other approaches based on the CSS Transforms module are presented below.

Text transformation

Rotation

In what follows, we examine a range of textual phenomena which in some ways appear very similar to those examined above, and even overlap with them. We can categorize these as text transformation features, and suggest some strategies for encoding them based on the properties detailed in the CSS Transforms specification. The CSS Transforms module provides a complex array of properties, values and functions which can be used to rotate, skew, translate and otherwise transform textual and graphical objects. We can borrow this vocabulary in order to describe textual phenomena in a precise manner.

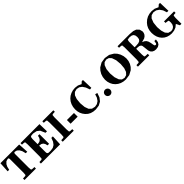

We begin with a simple example of a rotational transform:

Here a block of text has been rotated around its z-axis. This is clearly not a "writing mode"; the writing mode for this text is horizontal, left to right. Furthermore, even if we wished to treat this as a writing mode, we could not do so, because there is no way to use writing modes properties to describe an text orientation which is angled at 45 degrees; no human languages are consistently written in this orientation. It is more appropriate to treat this as a rotational transformation. We can do this using two properties: transform and transform-origin. (Both of these properties have quite complex value sets, and we will not look at all of them here. See the specification for full details.)

The transform property takes as its value one or more of the transform functions, one of which is the function rotateX:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateX(45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

Any rotation must take place around an axis positioned relative to the element being rotated, and the transform-origin property can be used to specify the pivot point. By default, the value of transform-origin is "50% 50%", the point at the centre of the element, but these values can be changed to reflect rotation around a different origin point.

An element may also be rotated about either of its other axes. For example, this shows rotation around the Y (vertical) axis:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab style="transform:rotateY(-45deg)">TEI-C.ORG</ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

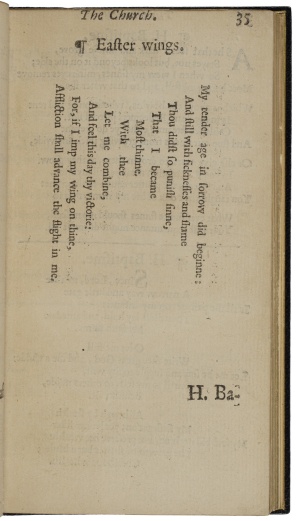

These are obviously trivial examples, but similar features do appear in historical texts. George Herbert's The Temple includes two stanzas headed "Easter Wings" which are both printed in a rotated form:

This could be encoded with:

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<lg style="transform:rotateX(90deg)"> <l>My tender age in ſorrow did beginne:</l> <l>And ſtill with ſickneſſes and ſhame</l> </lg>

</syntaxhighlight>

but we might also argue that this is in fact a vertical writing mode, and express it with writing-mode: vertical-rl; text-orientation: sideways-right.

Boustrophedon

We may also use rotation as a method of handling a true writing mode which is not covered by the CSS Writing Modes: boustrophedon. This is a writing mode common in inscriptions in Latin, Greek and other languages, in which alternate lines run from left to right and from right to left; its name derives from the path of an ox pulling a plough. Right-to-left lines in boustrophedon have another unexpected feature: their glyphs are reversed, so that these lines appear as "mirror writing". This examples shows a transcription of a Greek inscription at Dodona:

This might be transcribed as follows (ignoring word boundaries for the moment):

<syntaxhighlight lang="xml">

<ab> ΗΕΡΜΟΝΤΙΝΑ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΚΑΘΕΟΝΠΟΤΘΕΜ</seg> <lb/> ΕΝΟΣΥΕΝΕΑϜ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΟΙΥΕΝΟΙΤΙΕΚΚ</seg> <lb/> ΡΕΤΑΙΑΣΟΝΑ <lb/> <seg style="rotateY(180deg)">ΣΙΜΟΣΟΤΤΑΙΕ</seg> <lb/> ΑΣΣΑΙ </ab>

</syntaxhighlight>

The 180-degree rotation around the Y (vertical) axis here gives us exactly the effect of the RTL line in boustrophedon; the order of glyphs is reversed, and so is their individual orientation (in fact, we see them "from the back", as it were). <seg> elements have been used here because these are clearly not "lines" in the sense of poetic lines; the text is continuous prose, and linebreaks are incidental.

There are obviously some unsatisfactory aspects of this manner of encoding boustrophedon. In the inscription above, some words run across linebreaks, so if we wished to tag both words and the right-to-left phenomena, one hierarchy would have to be privileged over the other. By using a transform function rather than a writing mode property, we are apparently suggesting that boustrophedon is not in fact a writing mode, whereas it clearly is. But the CSS Writing Modes specification does not provide support for boustrophedon, because it is a rather obscure historical phenomenon; using a rotational transform is one practical alternative.

Caveats

The effect and behaviour of CSS Transforms properties and values according to the specification is highly dependent on the computed Visual formatting model of an HTML document. TEI does not have an explicit processing or formatting model, so it is by no means clear whether any given TEI element should be interpreted, for instance, as a block-level or inline-level element. For many elements we may think we can assume block-level (<ab>, "anonymous block") or inline-level (<w>, "word") from the semantics, but even this is risky. As long as the properties and values from the CSS Transforms module are used as a convenient, well-specified descriptive language to capture features of a text, without any expectation of using them directly and reliably for rendering, this is not problematic; we are simply borrowing a useful vocabulary from an external source, and benefiting from the clarity of definition provided by the specification. However, if there is any expectation of using this information to render a text in a predictable and accurate way, it will be essential to provide enough styling information throughout the document hierarchy to resolve all ambiguities with regard to size, positioning, block status, etc. before any element undergoes a transform operation.